Some readers will recall the easiest verse in the bible to memorize: “Jesus wept.” (Surely, you’re not going to interrupt this narrative by looking it up, but just in case, go to John 11:35.) Jesus has heard that one of the Lazaruses in the bible has died, and he intends to resurrect him. But before he performs this act, he weeps.

I’ve always thought he wept because Lazarus was better off dead, and Jesus was truly sorry he had to bring him back to this rat’s nest of a planet just to soothe the grief of Laz’s family and to prove that he, Jesus, could do such things. “If you knew what I knew,” I imagine Jesus saying, “you’d leave him where he is.”

The still unnamed faery’s child, too, knows she must now return the Knight to the land of the living. A grot is no place for a human to stay. “You’ve been here, you’ve experienced me, but you can’t camp out. You say we’re in love, but that has nothing to do with your making a career or a life of it. It has nothing to do with extending it in time, because love happens in Eternity which is outside of time. I’ll miss you – and that’s why I’m weeping in English – but go and love again. Or, if it makes you feel better, you can just mope and palely loiter on the cold hillside.”

|

| Pale Harold, learning to play Maude's banjo, tries to "go and love again" in Harold and Maude |

So what really lasts are the things that don’t, because we never forget them, so they’re always present.

That’s my take. But whatever the Knight hears in her weeping, it prompts him to “shut her wild wild eyes / With kisses four.” (Why four? In a letter, Keats gave two reasons: He wanted the kisses to be symmetrical, privileging neither eye, and he needed a rhyme for “sore.” Plus, he thought “a score” would be overdoing it. Seriously.)

The Knight’s “I” has returned. He feels the need to assert Self again. Why? Because he feels this bliss may go away if he doesn’t. He needs to “be there” to retain it. Her wild eyes would certainly invite kissing, but the verb is “shut.” My God. “Don’t see me”? “Don’t be awake”? Who hasn’t tried to keep his eyes closed to prolong a dream or to close them tightly again to restart it?

Some readers will argue that the earlier horse ride was only suggestive of sex, reflecting the sensual nature of the attraction. Instead of saying “They’re doing it,” the image of the ride was saying “This is what one or both of them would like to happen. This is not an attraction based on how the two feel about the world’s important issues.” I find this argument convincing and believe that the Knight’s intent is now, for the first time, to make love to this still unnamed faery’s child as if she were a human woman.

Haven’t we already established that we shouldn’t ask empirical questions about a story that includes a faery? Is “can faeries have intercourse with humans” an empirical question? Or is “do faeries need to have sex?” or “do faeries even have genitalia?”

Given Keats’s propensity for exacerbating the Romeo-and-Juliet problem a step farther (see “Lamia,” “Endymion,” and “The Eve of St. Agnes”), maybe we should ask those questions. Depending on our answers, these two could be about as star-crossed and hopeless as any lovers in literature.

Is there any chance that this couple, as a couple, can survive this encounter? If this were a Victorian novel, they’d have to wind up married. How will the Knight’s parents respond when he informs them he plans to marry an unnamed faery’s child who brings zilch in the way of a dowry? What about when his friends read the wedding announcement in the Sunday edition of the Camelot Herald? A faery? Faeries aren’t usually the friends of Knights.

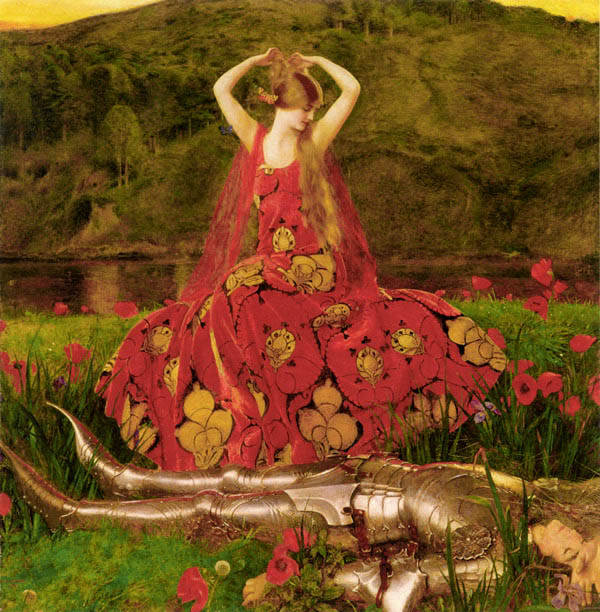

|

| Frank Cadogan Cowper's Dame dances by the depleted Knight and simultaneously checks her deoderant's efficacy. |

To continue with the Victorian novel, a consummation would need to take place off stage to assist in the continued growth of the empire. But do faeries have bodies one can actually physically consummate with? Can’t you see through faeries? My friends who believe in faeries say you can and faeries don’t need to do any messy biological things to reproduce. Plus they say they’re immortal. The odds are that the faery’s child will outlive her husband long, long after his pension has run dry.

The Knight, too, is pale and we earlier connected that to his experience with the faery’s child. Is she a femme fatale on steroids, a succubus who has drained his élan vital, leaving him “dry as hay” to “peak and pine,” as the first Weyard sister in Macbeth plans to do to a sailor?

And if so, has she also depleted the kings, princes and warriors? And why doesn’t the Knight see pale peasants, cooks and merchants in the dream? Why are they all men of power? And is the faery’s child making him dream this? Is this a dream or a vision? What’s the difference? If it’s a dream, does it mean anything? Are all dreams either about wishes or fears? Or are they pointless like the ones we hear almost daily either at home or work, surreal desultory epics, peopled and animaled with shape-shifting, free falls, aborted flights and psycho killers? Is it possible for dreams in poems to be pointless?

Too many questions, I know, but the interpretation of the poem rests on the answers. I believe Keats gives the Knight a dream born out of his, the Knight’s, anxiety which has been generated out of too much happiness. When we are too happy, we are afraid even to say the word “happy,” fearing it will break the enchantment, because we’ve come to think of happiness this way, as not being a normal part of existence, just some flickering temporary magic, so don’t say anything, don’t breathe, don’t get used to it.

I think of Othello reunited with Desdemona on the shores of Cyprus when he says, in essence, let me go ahead and die now because I’m afraid I’ll never be any happier than this. How to go on living when the greatest happiness is behind?

I will now soil this otherwise lofty narrative with words from that great Bard of the American Midwest, John Cougar: “Oh yeah, life goes on / Long after the thrill of livin’ is gone.”

So the Knight’s dream tells him, from people whose judgment he is most likely to value, he is happier than a human being has a right to be. They convince him that it is only a trick, a lethal one at that: “They cried, ‘La belle dame sans merci / Thee hath in thrall.’”

|

| The Knight enthralled |

The men of power have given the faery’s child a name, but consider the source. Of course, these guys are going to call her “la belle dame sans merci” – typically translated “the beautiful woman without pity or mercy” as opposed to “without thanks.” And by “these guys,” I mean the allegorical stand-ins for the Knight’s Excessive Happiness Anxiety (EHA) or Too Good to Be True Syndrome (TGBTS) or the personifications of his timid, overly cautious, earth-bound conscience telling him “You shouldn’t be doing this.”

After the ghastly images of these wan weenies’ yakking mouths, the Knight awakes and finds himself where we and the nameless narrator first found him, the “cold hill side.” The final stanza employs the incremental repetition typical of ballads, bringing the poem full circle:

And this is why I sojourn here

Alone and palely loitering;

Though the sedge is wither’d from the Lake

And no birds sing --

The first line answers the no-named narrator’s question posed in the first stanza. The last three lines essentially repeat the final three of that stanza, saying, in effect, “Your description is accurate. I am as you said.” The Knight’s repetition of the narrator’s words is as close as we’ll get to seeing him (the narrator) again. Who was he? Where did he go? Whatever happened to him?

Who gives a shit? No one sings the song of an ordinary man. I am reminded of the last words Susan Alexander says to the faceless Thompson near the end of Citizen Kane. After she has given her account – painful in its honesty – of Kane’s life, she gazes up at the skylight toward the dawning of a new day, blows a cloud of smoke, and says to him, “Come around and tell me the story of your life sometime.” Anyone want to hear that one?

As for the Knight, he resides in the not-so-sweet hereafter, suffering the possibly lethal symptoms of Keatsian Withdrawal or the Keatsian Twilight Zone or just plain old “reentry.”

You’ve seen this in literature and life. See Charles Smithson in the final chapters of French Lieutenant’s Woman; see Jay Gatsby had he been able to get out of his pool in time; see Harold at the end of Harold and Maude; see Cecilia at the end of Woody Allen’s Purple Rose of Cairo. See me when I return from Japan and find myself in an airport elevator filled with sweating, obese Americans complaining about the tiny portions of in-flight service.

Had this been written by someone other than Keats, we would now set out to determine if what happened to the Knight was a good thing or a bad thing. But Keats enjoyed holding two apparently contradictory ideas in his head simultaneously, and he enjoyed teasing his readers into an argument, then giving them ample evidence to support both the pros and the cons. I could easily, for example, argue that in “Grecian Urn,” life on the urn, in art, in the Ideal is preferable to life on earth, in nature, in “the real.” Having made that argument, I could then go back through the poem and make an equally convincing case for the other side.

Likewise for “La Belle.” “Palely,” “haggard,” and “woe begone” combined with faery and elfin imagery are all menacing and sinister, and suggest the Knight is lucky to be alive, that he has survived – for now! – a terrible evil. Seduced by the temptress faery, he has dared, like Dr. Frankenstein, to cross over into the forbidden supernatural world. He has responded to the songs of the Sirens, and now his ship has crashed into the rocks.

On the other hand, the faery’s child is “full beautiful,” and Keats claims in a letter that “What the Imagination seizes as Beauty, must be Truth,” and, of course, in “Grecian Urn” the narrator claims that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”

If we hunger for Beauty, we hunger for truth, and vice versa. Maybe the roots, honey and manna the Knight receives from the faery is our proper diet, the only one that truly nurtures us, the one we should’ve been eating all along. Note that the pale kings, princes and warriors warn the Knight with “starv’d lips,” perhaps because, assuming the faery’s food is toxic, they have deprived themselves of it.

Maybe the “too much happiness” feared by Othello and Keats’s men of power is what calls to us from the Other Side. It is real, the only reality worth living for. Maybe it calls us, not only to come over, but to bring it back with us, incarnate, if you will, to be a “friend to man,” to lift our thoughts and soothe our cares, “here and now where men sit and hear each other groan; / Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs, / Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies.”

Maybe, then, the pale Knight will recover from this painful withdrawal and go on to . . . .

Oh, how the hell would I know? Maybe he’d want to go back to the grot. Maybe he’s sorry for whatever he did that ejected him from his ecstasy. Maybe next time he’ll not “assert Self,” he’ll not try to hold on to it in hopes it’ll stay forever. Maybe the little sliver of light seeping under the grot’s door (if a grot has doors) is as close as he wants to come to this world again.

“Sing your faery’s song, my beloved, La Belle Dame avec Merci, sing forever, even if I can’t understand a word of it.”

“La Belle Dame sans Mercy”

By John Keats

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has wither’d from the lake

And no birds sing.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

I see a lily on thou brow

With anguish moist and fever dew,

And on thy cheek a faded rose

Fast withereth too.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful -- a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too and fragrant zone;

She look’d at as she did love

And made sweet moan.

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna dew,

And sure in language strange she said --

“I love thee true.”

She took me to her elfin grot,

And there she wept and sigh’d full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

And there she lulled me asleep,

And there I dream’d – Ah! woe betide!

The latest dream I ever dream’d

On the cold hill side.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried -- “La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall.”

I saw their starv’d lips in the gloam

With horrid warning gaped wide;

And I awoke and found me here

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here

Alone and palely loitering;

Though the sedge has wither’d from the Lake

And no birds sing --

No comments:

Post a Comment